Alberto Sughi At the Complesso del Vittoriano, 21 Luglio - 23 Settembre 2007

Michael Monkhouse, Alberto Sughi at the Vittoriano

If you’re like me and talk of Modern Art gets you thinking of clever-little-me Andy Warhol flourishing a coke can and proclaiming it some kind of Zen revelation, then I suggest you check out the Sughi exhibition at Complesso del Vittoriano.

Sughi (born 1928) is one of Italy’s – make that the world’s – most underrated artists, and the Complesso is one of Rome’s best-organised artistic sites. So you’re in for a visual treat.

And yet as you walk in and see the usual neatly-written summary and watch the usual neatly-performed video introduction, you may think you’re back in Warhol country. All that talk of realism, abstractism, post-cubist-anti-post-modernism, it’s enough to give Germaine Greer a coronary. I humbly suggest you throw that away – unless you like that sort of thing – and immerse yourself in the work itself. Fortunately the exhibition is organised chronologically so you can follow the man’s development step by step before it all gets too much.

We start with the early, ‘realist’ period of the mid- to late-forties. A world where innocent, almost Lowry-esque photoshots of guys hanging around in bus stations suddenly explodes into dark, disturbing depictions of urban alienation. Worthy of Grosz, Braque, Picasso.

And alienation is what we feel as we enter the first step of his mature vision. It’s an image of life as we know and hate it. The life of the boxer sweating and heaving on the canvas. A life that’s stood still since the 1950s when we heard we never had it so good. A life of bars, cinemas, prostitutes, where no one ever looks at each other. Where their faces are too harrowed and fearful and just plain diffused even to look out at us the viewer. The first face we see is Sughi himself in a portrait dated 1975 but it’s too stylised, too close to di Chirico’s to meet us. Then it’s his wife, an equally distorted and worrying sight. Then we arrive at ‘Masks of the Cinema’, where the masks aren’t those of the actors dutifully reciting their tired lines – we don’t even see them – it’s the spectators themselves, frozen and isolated and self-hating. Finally we reach ‘City at Night’, a kaleidoscope of fiery backgrounds, women dancing, men drinking and a warning sign that hits you like a sledgehammer in the guts. It’s been compared to film where one shot dissolves into another, a technique Ingmar Bergman was then perfecting to haunting effect in ‘Summer with Monica’; it’s been considered a damning indictment of man’s isolation; but what strikes you now is how you can feel the general sense of unease, fear, horror crawling through the players and into you. It’s a disquieting moment. Which is surely the point.

As faces dissolve they turn into animals – a hag in ‘Nude on a Bed’ (1953), there are even legs swishing like a horse’s tail in ‘Old Woman’ (1954) – everyday objects are more real, more convincing, more human than the humans that surround them. Even the idyllic countryside strains of a Monet or the easel of Sughi himself are more plastic than we are. It’s a sense of dislocation where you reach out to touch something – anything – just to feel you exist at all. I’m reminded of Bergman again and his characters’ need to feel their own bodies for assurance. But the bodies here are dissolving. We may be ‘Men in a Cinema’ (1959) or ‘Guys in a Bar’ (1960) but there’s a crucifix hanging over us (‘Crucifix in a City’, 1959) and our Cavalry is not over. Nor will it ever be. When politicians suffer the same fate (‘Representatives of Italy’, 1960), this is not, as critics would smugly – and reductively – have us believe, a snide swipe at Italy’s parliamentary system: it’s evidence all ills, from the body personal to the body politic, arise from the same cancer of the soul. When the politician of ‘The Governing Classes’ (1965) – significantly in glasses – smiles shrewdly at his partner and in a single glance tells us as much as the entire works of Brecht, he still can’t look at him. Even – or especially – ‘Lovers in a Bar’ (1960) won’t look each other in the face. And such a concrete backdrop as ‘Lungotevere’ (1959-60) becomes a universal image of suffering. We run away into intimacy and when we see ‘Inside a Room’ (1961) and a prostitute looking dolefully out at us whilst her lover puts his clothes back on we’re reminded of J. D. Salinger (Holden watching as the whore pulls the dress over her head), Sylvia Plath (her lover disrobes and all she can think of is chicken-skin) and ‘The Graduate’ (Benjamin slowly takes his clothes back off as Mrs Robinson – her back to him – drags her tights back off). Eerily, as a ‘Woman Undresses’ (1963) and lies back on the bed in a flurry of clothes there are hints of Degas’ innocent ballet dancers; but ‘Woman in a Room’ (1963) dispels such idealism as the flurry becomes Munchian streaks aiming directly at her intimacy. Her face shows she may be another animal, but the dynamics of the painting show that men are more animalesque for looking at her in this way.

The first climax has to be the ironically-entitled ‘Historic Hour’ (1965), where we see Bacon-style spaces swirling and whirling round a procession of those politicians centred round the ambiguous figure of a judge. And the second climax has to be ‘Theatre of Italy’ (1983), where as in Fellini we see everybody – clown, politician, clergyman, dancer, drunkard – round the figure of a more ambiguous judge. Again, this is not social commentary: this is social comment. As Plath expressed at the end of her short life, we can continuously refigure ourselves in varying roles, but ultimately our end is always the same, ‘roping us in with its many sticks’.

Sughi follows this vision with the so-called ‘Green Period’ of 1971-3. Again, people try to interact with their environment, but before we start thinking Virgil’s ‘Eclogues’ or Constable’s ‘Haywain’ he takes us closer to the dislocations of Magritte, where the environment is far more tangible than we could ever hope to be. There are storm-clouds overhead, more in the style of Bocklin or Sartre. The horror continues with a grasp at ‘The Family’ in the cycle of 1980-82, where we start with another Munch reference with a dying parent, proceed to the ‘Pregnant Woman’ (1981) who can’t even feel company with a baby in her womb, and finish with ‘Family and Love’ (1981), which to Sughi means a husband desperately copulating as his son sleeps in the next room. The 1980s saw Sughi more ferocious than ever with ‘The Dinner’ series. This isn’t a Davincian ‘Last Supper’ or even a Christian Communion, it’s a bunch of fat bourgeois ladies stuffing phallic ice-creams into their gobs. Enough said.

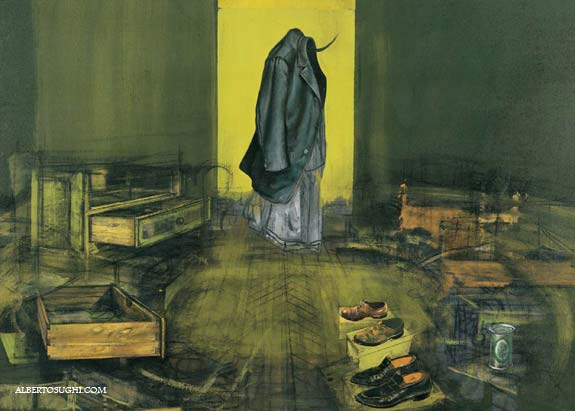

And so we approach the 1990s and the end of Sughi’s Odyssey, appropriately entitled ‘To Go – Where?’ Endless images of a man leaving a flaming building (‘Jane Eyre’, anyone?) with his bags neatly packed. Yet again, this has been read in an unnecessarily symbolic light – abandoning Communism, abandoning the fires of passion, abandoning oneself. I simply see it as Sughi’s own unceasing vision to find a new way forward without being able to relinquish the (emotional? Cultural? Psychological? It doesn’t matter) baggage of his past. After all, the first things he paints takes us right back to his roots: ‘Night, Women in a Bar’ (worthy of Hopper), ‘The Room of Time’ (backtracking), ‘Thirst’ (a man greedily thrusting at a tap in a painting with, disturbingly, the same name as one of Bergman’s first movies). Even ‘Balcony to the Sea’ shows a man out of contact with the beauty in front of him and ‘Artist’s Evening’ shows an artist out of joint with the instruments of art around him. Is that all we have left?

No, there’s one final shocker. Because the final phase – as I write – goes way back to the Renaissance and the Holy Family and even a Michelangelo pastiche. But in Sughi’s – our – world the lines are blurred and even artistic heritage proves shallow reward.

The exhibition runs till the end of September. If you still don’t want to see it I suggest a cold shower, a psychologist and a gander at Warhol.

Michael Monkhouse

August 2007